Multi-View Stereo based on Deep Learning

Multi-View Stereo (MVS) has become a key player in fields like 3D mapping, video games, and autonomous driving, allowing us to create detailed 3D reconstructions from multiple images. Recent advancements, especially those leveraging deep learning, have made MVS techniques more efficient and accurate. In this blog post, we'll dive into the latest methods shaping the future of MVS, with a particular focus on MVSNet and its successors. I'll break down how MVSNet works, covering essential steps like feature extraction, cost volume regularization, and reconstruction. At the end, there is a comparison how various models perform, using popular benchmarks like the DTU and Tanks and Temples datasets.

1. Introduction

In this blog, we examine the principles of multi-view stereo, a technique central to the generation of 3D models from multiple 2D images—a complex problem that has been the focus of research for many years.1 Tools like COLMAP 2 are one way to achieve precise three-dimensional representations from diverse image datasets. Traditional 3D reconstruction algorithms are relatively straightforward to implement, however, they are not without limitations, particularly when dealing with non-ideal conditions such as non-Lambertian surfaces, lacking abrupt color boundaries and uncalibrated camera sensors. However, the rise of Deep Learning (DL) and the exponential growth in computing power have dramatically transformed the landscape of scene reconstruction. These technological advancements have enabled the handling of vast datasets containing numerous scenes, facilitating easier comparison and evaluation of different reconstruction methodologies. This shift has been instrumental in circumventing the earlier constraints associated with non-Lambertian surfaces, opening up new possibilities for capturing and representing scenes under diverse and non-ideal conditions. The applications resulting from these advancements are diverse. They range from enriching immersive experiences in virtual reality environments to supporting the reconstruction of historical sites in archaeology and facilitating more accurate architectural designs.3

2. MVSNet

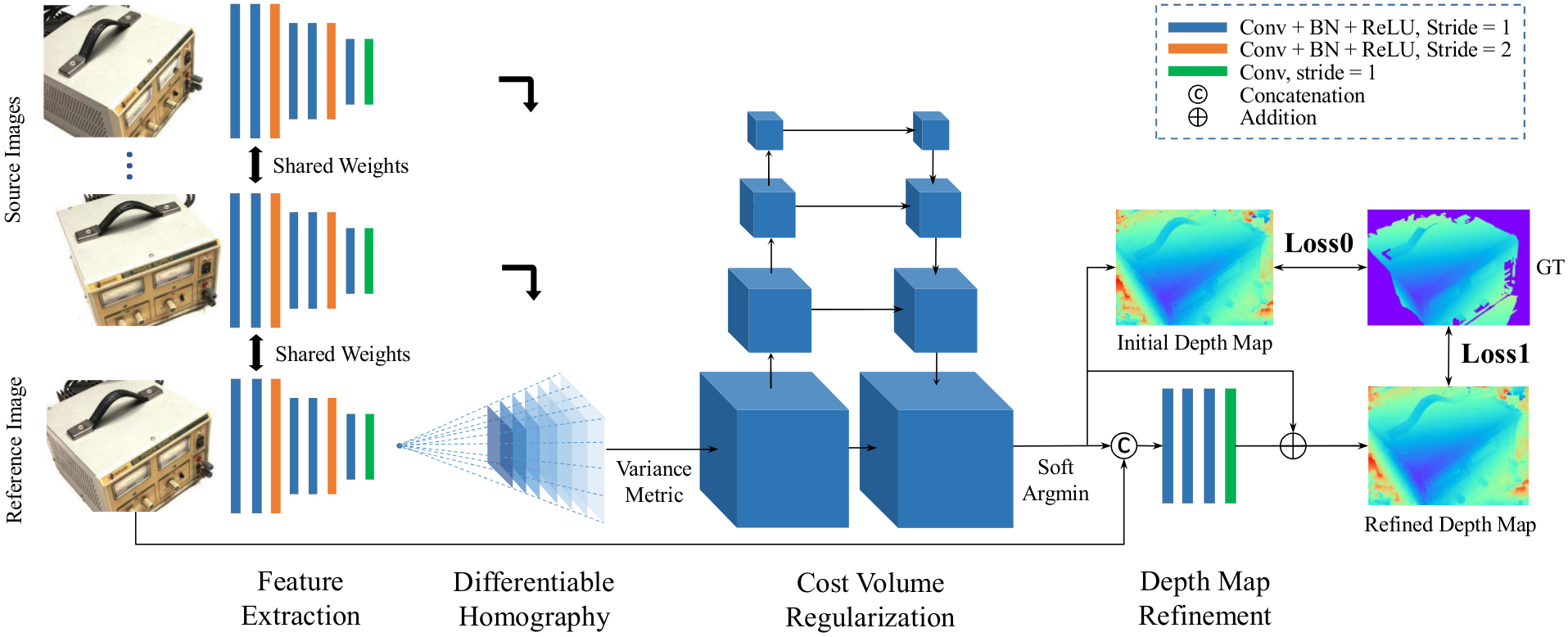

In the following, MVSNet by Yao et al. is introduced as the baseline model for this blog post.4 MVSNet is considered a successful early adopter of DL and is frequently cited in subsequent research. The architectural framework of MVSNet is comprehensively shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: Overview of MVSNet: (1) 2D Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) captures image features, (2) homography integrates multiple views, (3) cost volume computation aggregates corresponding information, and (4) refinement enhances depth map precision for robust depth map.4

First, MVSNet initiates its depth inference process by extracting deep visual image features of images through a simple multi-layer 2D CNN. At the third and sixth layers, the strides are set to two, effectively reducing the height and width of the feature space by a total factor of 4, respectively. These extracted features are then organized into a set, denoted by for each image . The feature extraction network is shared for all input images providing an efficient training mechanism for the model. Subsequently, the extracted features must be transformed into a cost volume. The cost volume is a data structure that incorporates geometric constraints and prior knowledge. The process is divided into three steps: (1) the computation of differentiable homography, (2) the formulation of a cost metric, and (3) the application of cost volume regularization.

To obtain such a cost volume, the authors relate the feature maps according to their homography. In particular, the feature maps undergo a transformation into frontoparallel planes with respect to the frustum of the reference view. The homography matrix considers for that camera intrinsics, rotations, and translations, denoted by respectively, where denotes the image (see eq. 1). The planar transformation relates then the coordinates of points at depth in one feature map to the coordinates of the reference feature map. Ultimately, the feature maps are converted into feature volumes of shape , where denots the depth, and the number of channels of the feature map.

The warping operation is formulated in a differentiable way, allowing end-to-end trainability.

Following step (1), in step (2) the feature volumes are aggregated along the feature channel dimension to obtain a single cost volume. The feature volumes could be aggregated using the mean (as shown in 5). Yao et al. instead choose to use the variance as it is able to capture feature differences (see eq. 2).

In step (3), the raw cost volume may contain some noise which leads to a performance drop. To address this issue the cost volume is being smoothed (regularized). To achieve this the authors apply a multi-scale 3D CNN, designed in a U-Net-like structure. The encoder-decoder construction allows to perceive and reinforce neighboring information. From that the normalized probability for each depth hypotheses is retrieved through the softmax function resulting in a probability volume. This probability volume has two purposes. First, it can be used for computing the depth of a single image as well as offering a confidence measure of the inference.

To derive an initial depth map there are two proposed operations. One could either apply the argmax function to the probability volume , or use the soft argmin (as suggested in 6). Since argmax is indifferentiable, end-to-end training cannot be employed. Hence, MVSNet uses the soft argmin. The soft argmin operation is the expected value along in depth direction and is being computed as follows:

returns the probability for all pixels being at depth .

Although the depth map can be considered final, it still may lack quality in different areas, i.e. oversmoothing at reconstruction boundaries. To overcome this issue, an additional network, a so-called depth residual learning network, is being deployed. The network takes the concatenation of the initial depth map and the resized reference image as an input. The objective of this model is to learn the depth residuals. The depth residuals are then added to the original depth map.

As seen in figure 1 two losses are being computed (see eq. 4). Yao et al. consider the mean absolute difference between the actual depth map and the initial depth map and between the actual depth map and the refined depth map . Pixels without any associated ground truth are excluded. Hence, only is being considered.

3. Modular optimization based on MVSNet

MVSNet has shown state-of-the-art performance on benchmarks due to many factors and effective utilization of DL and CNN advancements. The model's end-to-end training capability with minimal adjustments garnered community interest. While MVSNet demonstrated a novel architecture, it has not fully realized its maximum potential (see table 1). The modular design offers the possibility to replace certain parts of the architecture. Hence, numerous networks were published afterwards that excel in different categories. To systematically analyze these advancements, Zhu et al. propose to categorize MVS-algorithms into feature extraction, cost volume construction, and cost volume regularization.7 Seitz et al. break the properties of MVS-algorithms into scene representation, photo-consistency measure, visibility model, shape prior, reconstruction algorithm, and initialization requirements down.8 Especially the reconstruction algorithm is of interest since most models only infer a depth map, yet some benchmarks require a point-cloud instead. Therefore, reconstruction algorithms that perform such transformations, should be highlighted. In addition, the loss function should also be of interest. To sum up, the next section focuses on feature extraction, cost volume regularization, loss, and reconstruction.

3.1. Feature extraction network

MVSNet employs a simple 2D CNN (in a Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) style) for feature extraction. However, more complex architectures like U-Net or ResNet are better suited for feature extraction (as exemplified in 9 10).

GeoMVSNet integrates both approaches by iterating through images in multiple stages, progressing from low-resolution to full resolution.10 At each stage, geometric information from prior stages are incorporated at two distinct steps.

In the context of feature extraction, only the first step, namely leveraging prior geometric information in the feature extraction step, is of interest and will be highlighted. At the earliest stage, no prior information can be utilized. Therefore, the authors initially implement a basic FPN to extract features from the most downscaled version of the input images. These extracted features undergo a process resulting in a low-resolution depth map. This coarse depth map is then integrated into the feature extraction step for the next finer stage. Technically, this is done by processing the depth map as a 2D discrete signal, allowing to transform it into the frequency domain via the Discrete Fourier Transformation. A low-pass filter removes then high-frequencies before the frequency domain is inverted back. Consequently, the depth map considers a full-scene geometry perception, filtering out high-frequency signals and drastic misinformation. The "improved depth map" is then employed in the subsequent feature extraction. A branching mechanism combines the newly extracted features at higher resolution with the cleaned coarse depth from the previous stage, serving as a geometric prior. This iterative process enhances the model's ability to generate accurate depth maps throughout all later stages.

With the growing success of transformers in NLP, emerging networks for MVS, more novel models incorporate transformers into their feature extraction pipeline (such as those in 11 12 13 14). Transformers excel in capturing long-range dependencies and global contextual information.15 In contrast to CNNs, which process images in a grid-like fashion, Vision Transformers (ViT) treat the entire image as a sequence of tokens, allowing them to learn relationships between distant pixels.16 This global perspective proves beneficial in MVS scenarios where understanding spatial context across multiple views is crucial. A notable example illustrating this concept is MVSTR.14 Here the authors start by extracting features using a simple CNN network. These extracted features, along with their positional embeddings, are then passed into a global-context transformer as input, capturing long-range dependencies within each view. The output is subsequently fed into another transformer, the 3D-geometry transformer, which captures dependencies across multiple views. These transformers alternate for times to enhance the understanding of global and local information within and across multiple views. While ViTs are more scalable than CNNs, training them is challenging due to the substantial amount of data they require. Networks like MVSFormer highlight the importance of leveraging pre-trained ViTs.11

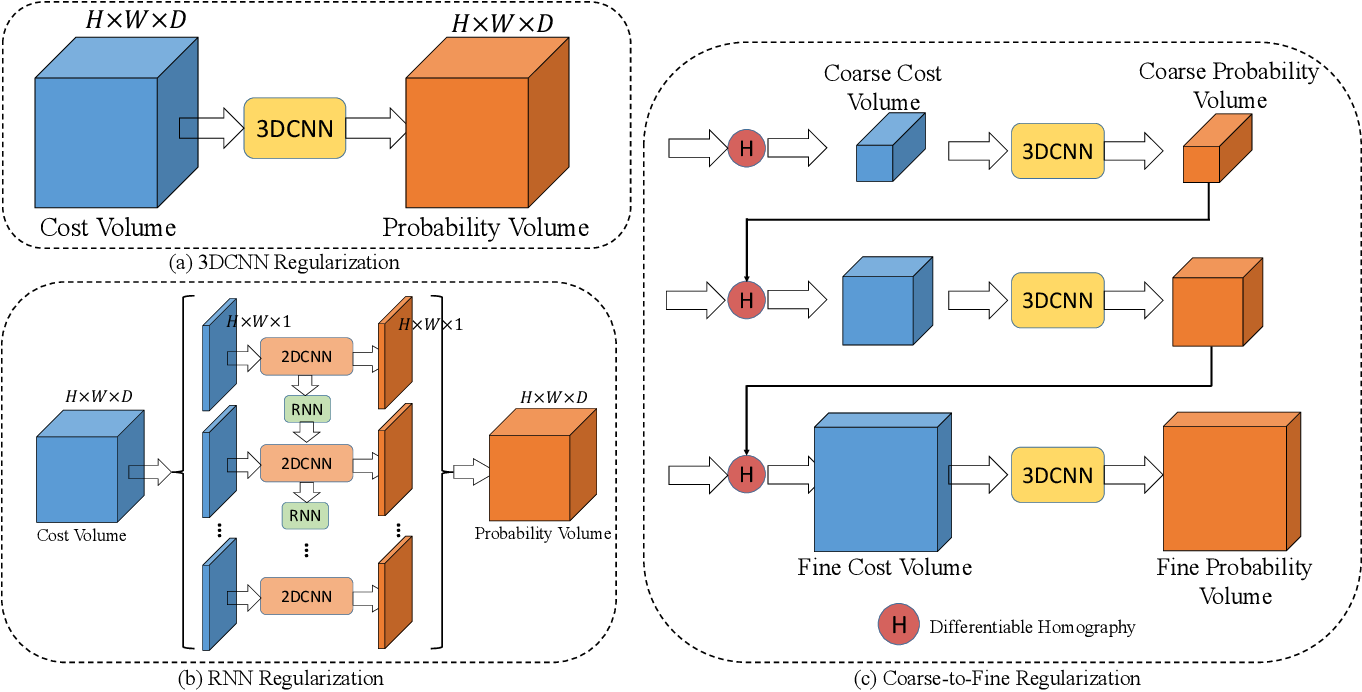

3.2. Cost volume regularization

A main distinction between MVS models can be found in the methodology that employs cost volume regularization. The strategies for designing cost volume regularization can be divided into three distinct approaches, namely, 3D CNN 4, Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) 17 18, and coarse-to-fine-approaches 19 20 21 22 23 24. Figure 2 provides visual representations.

Figure 2: Visual comparison of different cost volume regularization methods

3.2.1 3D CNN

MVSNet is an early adopter of a U-Net-like 3D CNN for cost volume regularization.4 The advantage of using 3D CNNs lies in its capability to combine both local and global features across all dimensions in .

3.2.2 RNN

However, 3D CNN are computationally expensive which limits its ability to use finer depths. For addressing the challenge of excessive memory usage, some models opt for a different approach by substituting 3D CNNs with sequential 2D CNNs along the depth dimension . RNN-approaches consider previous depth hypotheses by subsequently passing them as context information for later depths. This modification ensures that only one slice of the cost volume is processed in the GPU memory at a time reducing the memory issue, but also providing finer flexibility in scaling the dimension . Earlier techniques incorporate spatial information within a specific distance.25 R-MVSNet proposes cost volume regularization using Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU).18 GRUs are a RNN-architecture initially proposed for learning sequential text. It gathers spatial and uni-directional context information in the depth direction. To enhance regularization, R-MVSNet stacks three GRU layers. The cost volume is seen as cost maps in depth direction. After applying the recurrent regularization the result is , where depends on the current and previous cost maps . Before applying the GRUs, a convolutional layer is applied to retain context information. DHC-RMVSNet represents an additional approach.17 R-MVSNet, in comparison, experiences some loss regarding the context information. To tackle this issue DHC-RMVSNet introduces a 2D U-Net-like architecture, where each layer is a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) cell. This architecture enables the aggregation of multi-scale context information, reducing memory consumption down to only 19.4% of R-MVSNet, while efficiently processing dense original-size cost volumes.

3.2.3 Coarse-to-fine

One limitation of these RNN-based methods, however, is that they are less efficient with respect to parallelizability than traditional CNNs which can negatively impact the run time. Hence, models such as MVSNet, or R-MVSNet downscale the images to obtain a cost volume with lower resolution. From there the models upsample or implement post-refinement to generate a final result in high resolution. Coarse-to-fine approaches solve this by progressively refining the reconstruction by initially generating a rough approximation and iteratively improving the details through successive stages of increasing refinement.19 20 21 22 23 24 CasMVSNet proposes to use a cascade cost volume.21 The cost volume at the beginning is based on large scale semantic features selected from a sparse depth hypotheses. As a result, the resolution of the cost volume is lower. Based on this coarse cost volume, an initial depth map is determined. The resolution is then gradually refined by combining the preceding depth map and finer semantic features used as a basis for subsequent stages. This process can be repeated multiple times. With every iteration the range of hypothesis depths is improved and a new cost volume with finer semantic features is derived.

3.3. Loss

The loss function is a measure of the dissimilarity between the predicted depth map and the ground truth depth or disparity map. With regard to the loss function, there are two different related challenges, namely, regression and classification, as well as unsupervised methods.

3.3.1 Regression vs. Classification

In machine learning, the choice of a loss function plays an important role in determining the final prediction. The optimization problem can be framed in various ways, either as a regression problem (exemplified in 21 4), or as a classification issue (represented in 17 18 24). In classification problems, the argmax function is commonly employed, accompanied by the use of cross entropy as a loss function. However, the inherently less smooth nature of classification can result in unsteadiness in depth values. Conversely, regression tackles the optimization problem differently, utilizing loss functions such as , as seen in the equation 4. Since a model, that uses regression, needs to learn a complex combination of weights under indirect constraints performed on the weighted depth but not on the weight combination, it tends to overfit and increase the difficulty of the model convergence.26 Each approach reflects a distinct methodology in shaping the model's predictions.

3.3.2 Unsupervised Learning

Up to this point, the focus of this post has been on models trained through supervised learning. Nevertheless, numerous datasets are synthetically generated, presenting challenges in their creation. Consequently, unsupervised learning offers a valuable alternative, allowing models (such as 27 28 29) to be trained in theory on simpler datasets without the availability of provided ground truths.

This blog post will not dive into unsupervised learning in depth, but I can highly recommend the following articles:

- Medium: Unsupervised Multi-View Stereo — An Emerging Trend

- Medium: 3D Reconstruction News — AAAI 2021

4. Results

In the following, I will first introduce popular datasets/benchmarks and afterwards I will set some models side by side.

4.1. Datasets/Benchmarks and Metrics

There are several benchmarks one could use (e.g. 30 31 32 33 34 35 36). In the following, however, two of the most common datasets will be highlighted. The Tanks and Temples dataset comprises a collection of high-resolution images and corresponding depth maps captured from various indoor and outdoor environments.32 The dataset includes scenes with complex geometry ranging from an intermediate level to advanced difficulty, making it a valuable resource for evaluating stereo vision algorithms and depth estimation techniques. In addition, this dataset offers an online leaderboard. To compare the models with each other, the metric rank is introduced, which indicates the average rank across all scenes. In contrast, DTU is a multi-view stereo dataset containing 128 scans with 49 views under different lighting conditions, which doesn't offer any leaderboards.30

Similar to Tanks and Temples, this dataset provides the ground truth in a point-cloud format.

As many models are only capable of generating depth maps, the provided data must be converted to depth maps to even allow training. This is done by first converting the data into mesh models and then into depth maps. Usually, the screened Poisson surface reconstruction algorithm is used for this transformation.37 The fundamental objective of a model is to improve not only effectiveness but also efficiency. To measure the current performance level, metrics capture accuracy, completeness, GPU memory consumption, and run time. Accuracy, or precision, quantifies either the percentage of predicted points that align with the ground truth point-cloud or the mean/median distance, which applies to this report. Recall/Completeness measures either the proportion of ground truth points that are captured by the predicted point-cloud or the mean error distance between the closest points in the reconstruction and the ground truth. As before, the latter applies to this report. However, relying solely on either metric may not provide a comprehensive comparison due to different assumptions made by the methods. While stronger assumptions often lead to higher accuracy but lower completeness, both measures are essential for a fair comparison. The F-score, as a harmonic mean of precision and recall, fixes this.

4.2. Model Comparison

One notable limitation in our discussion is the absence of detailed information regarding GPU memory consumption and run-time across some of the models.

In evaluating the performance of MVS methods, the comparison with COLMAP2, a non-learning baseline, serves as a fundamental baseline. Analyzing the results in table 1, it becomes evident that DL-based MVS methods perform superior compared to traditional methods, particularly in terms of completeness. This applies, however, not for all DL-based models. Earlier models, such as SurfaceNet 38, were not able to outperform COLMAP. This changed with MVSNet. MVSNet, upon its release, demonstrated remarkable performance and briefly secured the top position in the Tanks and Temples benchmark.4 Taking a closer look at the difference between methods employing either a RNN or a coarse-to-fine approach to cost volume regularization, one can observe an asymmetrical performance. On the DTU dataset, coarse-to-fine methods (such as 19 20 21 22 23 24) perform better than RNN-based models (such as 17 18), but achieve worse results on the Tanks and Temple benchmark. A plausible explanation for this disparity lies in the nature of the datasets themselves. DTU, with its emphasis on complex details, provides an environment where coarse-to-fine methods excel by recognizing subtle depth differences. Conversely, looking at Tanks and Temples, characterized by a larger scale, RNN methods prove superior, leveraging their ability to use a larger depth scale. In the context of inference time and memory consumption, coarse-to-fine methods perform better than 3D CNN. This progress is achieved without compromising performance metrics, thereby reflecting an improvement in efficiency and effectiveness.

As of November 2023, MVSFormer11 currently holds the top position on the Tanks and Temples leaderboard, closely accompanied by similar approaches like ET-MVSNet39. From this observation, it can be speculated that methods employing transformers, such as ViTs, for feature extraction combined with coarse-to-fine regression exhibit superior performance compared to alternative approaches.

| Method | Acc. (mm) | Comp. (mm) | Overall (mm) | GPU Memory (GB) | Run-time(s) | Rank | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COLMAP 2 | 0.400 | 0.664 | 0.532 | - | - | 357.00 | 42.14 |

| SurfaceNet 38 | 0.450 | 1.040 | 0.745 | - | - | 422.50 | 26.30 |

| MVSNet (D=192) 4 | 0.456 | 0.646 | 0.551 | 10.8 | 1.210 | 358.25 | 43.48 |

| Fast-MVSNet 24 | 0.336 | 0.403 | 0.307 | 5.3 | 0.6 | 341.62 | 47.39 |

| R-MVSNet 18 | 0.383 | 0.452 | 0.417 | 6.7 | 9.1 | 337.88 | 48.40 |

| DHC-RMVSNet (D=512) 17 | 0.395 | 0.378 | 0.386 | - | - | 140.88 | 59.20 |

| GeoMVSNet 10 | 0.331 | 0.259 | 0.295 | - | - | 16.88 | 65.89 |

| Point-MVSNet 19 | 0.342 | 0.411 | 0.376 | 8.7 | 3.35 | 331.50 | 48.27 |

| CasMVSNet 21 | 0.325 | 0.385 | 0.355 | 5.3 | 0.492 | 199.88 | 56.84 |

| MVSTR 14 | 0.356 | 0.295 | 0.326 | 3.9 | 0.81 | 223.38 | 56.93 |

| MVSFormer 11 | 0.327 | 0.251 | 0.289 | - | - | 13.38 | 66.41 |

| ET-MVSNet 12 | 0.329 | 0.253 | 0.291 | - | - | 20.75 | 65.49 |

| MVS 27 | 0.760 | 0.515 | 0.637 | - | - | 396.00 | 37.21 |

| M3VSNet (D=192) 28 | 0.636 | 0.531 | 0.583 | - | - | 395.25 | 34.03 |

Table 1: Comparison of the performance of different methods for MVS on two popular datasets: DTU and Tanks and Temples. The methods are evaluated based on four metrics: accuracy, completeness, overall error, and GPU memory consumption. This comparison also reports the run time and the rank of each method on the Tanks and Temples leaderboard as of November 2023. The best value in each category is highlighted in bold.

5. Conclusion

In summary, this exploration of MVS based on DL focused on the foundational MVSNet model, dissecting its components and identifying the following key properties: feature extraction, cost volume regularization, loss, and reconstruction. This understanding made it possible to identify and examine various approaches that aimed to enhance specific aspects, such as feature extraction, regularization, and reconstruction. The landscape of MVS has witnessed progress within theses categories. The comparison of these models on public benchmarks provided a quantitative measure of their performance, highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of each approach. In essence, this blog post underscores the remarkable progress made in DL-based MVS.

Footnotes

-

Gregory G. Slabaugh, W. Bruce Culbertson, Thomas Malzbender, and Ronald W. Schafer. A survey of methods for volumetric scene reconstruction from photographs. In Klaus Mueller and Arie E. Kaufman, editors, 2nd IEEE TCVG / Eurographics International Workshop on Volume Graphics, VG 2001, Stony Brook, NY, USA, June 21-22, 2001, pages 81–101. Eurographics Association, 2001. ↩

-

Johannes L. Schönberger and Jan-Michael Frahm. Structure-from-motion revisited. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Com- puter Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2016, Las Vegas, NV, USA, June 27-30, 2016, pages 4104–4113. IEEE Computer Society, 2016. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Yasutaka Furukawa and Carlos Hern´andez. Multi-view stereo: A tutorial. Found. Trends Comput. Graph. Vis., 9(1-2):1–148, 2015. ↩

-

Yao Yao, Zixin Luo, Shiwei Li, Tian Fang, and Long Quan. MVSNet: Depth inference for unstructured multi-view stereo. CoRR, abs/1804.02505, 2018. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7

-

Wilfried Hartmann, Silvano Galliani, Michal Havlena, Luc Van Gool, and Konrad Schindler. Learned multi-patch similarity. In IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2017, Venice, Italy, October 22-29, 2017, pages 1595–1603. IEEE Computer Society, 2017. ↩

-

Alex Kendall, Hayk Martirosyan, Saumitro Dasgupta, and Peter Henry. End-to-end learning of geometry and context for deep stereo regression. In IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2017, Venice, Italy, October 22-29, 2017, pages 66–75. IEEE Computer Society, 2017. ↩

-

Qingtian Zhu. Deep learning for multi-view stereo via plane sweep: A survey. CoRR, abs/2106.15328, 2021 ↩

-

Steven M. Seitz, Brian Curless, James Diebel, Daniel Scharstein, and Richard Szeliski. A comparison and evaluation of multi-view stereo reconstruction algorithms. In 2006 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2006), 17-22 June 2006, New York, NY, USA, pages 519–528. IEEE Computer Society, 2006. ↩

-

Jinli Liao, Yikang Ding, Yoli Shavit, Dihe Huang, Shihao Ren, Jia Guo, Wensen Feng, and Kai Zhang. Wt-mvsnet: Window-based transformers for multi-view stereo. In NeurIPS, 2022. ↩

-

Zhe Zhang, Rui Peng, Yuxi Hu, and Ronggang Wang. Geomvsnet: Learning multi-view stereo with geometry perception. In IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2023, Vancouver, BC, Canada, June 17-24, 2023, pages 21508–21518. IEEE, 2023. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Chenjie Cao, Xinlin Ren, and Yanwei Fu. MVSFormer: Multi-view stereo by learning robust image features and temperature-based depth. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res., 2022, 2022 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Tianqi Liu, Xinyi Ye, Weiyue Zhao, Zhiyu Pan, Min Shi, and Zhiguo Cao. When epipolar constraint meets non-local operators in multi-view stereo. CoRR, abs/2309.17218, 2023. ↩ ↩2

-

Haofei Xu, Jing Zhang, Jianfei Cai, Hamid Rezatofighi, Fisher Yu, Dacheng Tao, and Andreas Geiger. Unifying flow, stereo and depth estimation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell., 45(11):13941–13958, 2023. ↩

-

Jie Zhu, Bo Peng, Wanqing Li, Haifeng Shen, Zhe Zhang, and Jianjun Lei. Multi-view stereo with transformer. CoRR, abs/2112.00336, 2021. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez, Lukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. Attention is all you need. In Isabelle Guyon, Ulrike von Luxburg, Samy Bengio, Hanna M. Wallach, Rob Fergus, S. V. N. Vishwanathan, and Roman Garnett, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, December 4-9, 2017, Long Beach, CA, USA, pages 5998–6008, 2017. ↩

-

Alexey Dosovitskiy, Lucas Beyer, Alexander Kolesnikov, Dirk Weissenborn, Xiaohua Zhai, Thomas Unterthiner, Mostafa Dehghani, Matthias Minderer, Georg Heigold, Sylvain Gelly, Jakob Uszkoreit, and Neil Houlsby. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In 9th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2021, Virtual Event, Austria, May 3-7, 2021. OpenReview.net, 2021. ↩

-

Jianfeng Yan, Zizhuang Wei, Hongwei Yi, Mingyu Ding, Runze Zhang, Yisong Chen, Guoping Wang, and Yu-Wing Tai. Dense hybrid recurrent multi-view stereo net with dynamic consistency checking. In Andrea Vedaldi, Horst Bischof, Thomas Brox, and Jan-Michael Frahm, editors, Computer Vision - ECCV 2020 - 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23-28, 2020, Proceedings, Part IV, volume 12349 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 674–689. Springer, 2020. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

Yao Yao, Zixin Luo, Shiwei Li, Tianwei Shen, Tian Fang, and Long Quan. Recurrent MVSNet for high-resolution multi-view stereo depth inference. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2019, Long Beach, CA, USA, June 16-20, 2019, pages 5525–5534. Computer Vision Foundation / IEEE, 2019. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

Rui Chen, Songfang Han, Jing Xu, and Hao Su. Point-based multi-view stereo network. In 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2019, Seoul, Korea (South), October 27 - November 2, 2019, pages 1538–1547. IEEE, 2019. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Shuo Cheng, Zexiang Xu, Shilin Zhu, Zhuwen Li, Li Erran Li, Ravi Ramamoorthi, and Hao Su. Deep stereo using adaptive thin volume representation with uncertainty awareness. In 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2020, Seattle, WA, USA, June 13-19, 2020, pages 2521–2531. Computer Vision Foundation / IEEE, 2020. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Xiaodong Gu, Zhiwen Fan, Siyu Zhu, Zuozhuo Dai, Feitong Tan, and Ping Tan. Cascade cost volume for high-resolution multi-view stereo and stereo matching. In 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2020, Seattle, WA, USA, June 13-19, 2020, pages 2492–2501. Computer Vision Foundation / IEEE, 2020. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6

-

Alexander Rich, Noah Stier, Pradeep Sen, and Tobias Höllerer. 3DVNet: Multi-view depth prediction and volumetric refinement. In International Conference on 3D Vision, 3DV 2021, London, United Kingdom, December 1-3, 2021, pages 700–709. IEEE, 2021. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Jiayu Yang, Wei Mao, José M. Álvarez, and Miaomiao Liu. Cost volume pyramid based depth inference for multi-view stereo. In 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2020, Seattle, WA, USA, June 13-19, 2020, pages 4876–4885. Computer Vision Foun- dation / IEEE, 2020. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Zehao Yu and Shenghua Gao. Fast-MVSNet: Sparse-to-dense multi-view stereo with learned propagation and gaussnewton refinement. In 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2020, Seattle, WA, USA, June 13-19, 2020, pages 1946–1955. Computer Vision Foundation / IEEE, 2020. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

Qingxiong Yang. A non-local cost aggregation method for stereo matching. In 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Providence, RI, USA, June 16-21, 2012, pages 1402–1409. IEEE Computer Society, 2012. ↩

-

Rui Peng, Rongjie Wang, Zhenyu Wang, Yawen Lai, and Ronggang Wang. Rethinking depth estimation for multi-view stereo: A unified representation. In IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2022, New Orleans, LA, USA, June 18-24, 2022, pages 8635–8644. IEEE, 2022. ↩

-

Yuchao Dai, Zhidong Zhu, Zhibo Rao, and Bo Li. MVS2: deep unsupervised multi-view stereo with multi-view symmetry. In 2019 International Conference on 3D Vision, 3DV 2019, Québec City, QC, Canada, September 16-19, 2019, pages 1–8. IEEE, 2019. ↩ ↩2

-

Baichuan Huang, Hongwei Yi, Can Huang, Yijia He, Jingbin Liu, and Xiao Liu. M3VSNET: unsupervised multi-metric multi-view stereo network. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, ICIP 2021, Anchorage, AK, USA, September 19-22, 2021, pages 3163–3167. IEEE, 2021. ↩ ↩2

-

Tejas Khot, Shubham Agrawal, Shubham Tulsiani, Christoph Mertz, Simon Lucey, and Martial Hebert. Learning unsupervised multi-view stereopsis via robust photometric consistency. CoRR, abs/1905.02706, 2019. ↩

-

Henrik Aanæs, Rasmus Ramsbøl Jensen, George Vogiatzis, Engin Tola, and Anders Bjorholm Dahl. Large-scale data for multiple-view stereopsis. Int. J. Comput. Vis., 120(2):153–168, 2016. ↩ ↩2

-

Andreas Geiger, Philip Lenz, and Raquel Urtasun. Are we ready for autonomous driving? the KITTI vision benchmark suite. In 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Providence, RI, USA, June 16-21, 2012, pages 3354–3361. IEEE Computer Society, 2012. ↩

-

Arno Knapitsch, Jaesik Park, Qian-Yi Zhou, and Vladlen Koltun. Tanks and temples: benchmarking large-scale scene reconstruction. ACM Trans. Graph., 36(4):78:1–78:13, 2017. ↩ ↩2

-

Moritz Menze and Andreas Geiger. Object scene flow for autonomous vehicles. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2015, Boston, MA, USA, June 7-12, 2015, pages 3061–3070. IEEE Computer Society, 2015. ↩

-

Daniel Scharstein, Heiko Hirschmüller, York Kitajima, Greg Krathwohl, Nera Nesic, Xi Wang, and Porter Westling. High-resolution stereo datasets with subpixel-accurate ground truth. In Xiaoyi Jiang, Joachim Hornegger, and Reinhard Koch, editors, Pattern Recognition - 36th German Conference, GCPR 2014, Münster, Germany, September 2-5, 2014, Proceedings, volume 8753 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 31–42. Springer, 2014. ↩

-

Thomas Schöps, Johannes L. Sch¨onberger, Silvano Galliani, Torsten Sattler, Konrad Schindler, Marc Pollefeys, and Andreas Geiger. A multi-view stereo benchmark with high-resolution images and multi-camera videos. In 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2017, Honolulu, HI, USA, July 21-26, 2017, pages 2538–2547. IEEE Computer Society, 2017. ↩

-

Tao Sun, Mattia Segù, Janis Postels, Yuxuan Wang, Luc Van Gool, Bernt Schiele, Federico Tombari, and Fisher Yu. SHIFT: A synthetic driving dataset for continuous multi-task domain adaptation. In IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2022, New Orleans, LA, USA, June 18-24, 2022, pages 21339–21350. IEEE, 2022. ↩

-

Michael M. Kazhdan and Hugues Hoppe. Screened poisson surface reconstruction. ACM Trans. Graph., 32(3):29:1–29:13, 2013. ↩

-

Mengqi Ji, Juergen Gall, Haitian Zheng, Yebin Liu, and Lu Fang. Surfacenet: An end-to-end 3d neural network for multiview stereopsis. In IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2017, Venice, Italy, October 22-29, 2017, pages 2326–2334. IEEE Computer Society, 2017. ↩ ↩2

-

Tianqi Liu, Xinyi Ye, Weiyue Zhao, Zhiyu Pan, Min Shi, and Zhiguo Cao. When epipolar constraint meets non-local operators in multi-view stereo. CoRR, abs/2309.17218, 2023. ↩